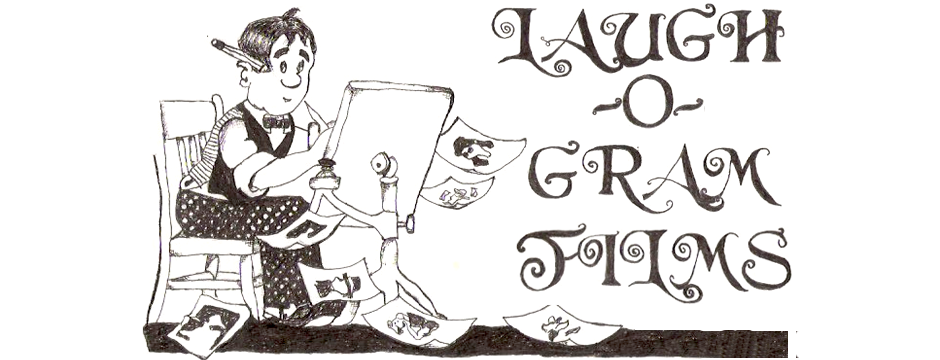

Created in 1921, “this short film, variously labeled a test reel, sample reel, or the series pilot, was made as a filler for Frank Newman’s local Kansas City theater chain, and is the only Newman Laugh-O-gram known to survive. It could scarcely be simpler. But the opening image of Disney himself, the portrait of the artist as a young impresario, has an uncanny feel to it. Disney begins his animation career with multiple pictures of himself, the live image sandwiched between two self-caricatures. We see him first as part of the comic title card, a wide-eyed innocent at his desk, his sleeves rolled up and papers flying from his pen. Then, the live-action Disney puts the title card into motion, scratching his head, lighting his pipe, and applying pen to paper. Meanwhile, over his right shoulder we notice another drawing of him (a jumbo version of his actual business card), a third version of Disney the hard-pressed cartoonist working at his office desk, while we see the results of all his work hanging over his left shoulder – four sequential drawings of a figure we’ll see animated at the end of the reel.

…

Like all the Laugh-O-gram films made for Newman, this one was made by Disney single-handedly, and so provides a rare chance to see Disney’s own early animation style. This would change quickly, as Disney recruited friends to share the work. Here, though, completing each drawing on paper fully by hand (he had yet to learn the labor-saving techniques associated with cel animation), he in fact animates only the final sequence. If he tries to separate himself from the traditions of the lightning-sketch artist in his self-portrait, he immerses himself in them in the opening scenes, including the convention of showing his hand rapidly creating the drawings. In fact, it is a photograph of his hand, the hyperactivity of the artist recreated one last time through the magic of stop-motion.”

Excerpt from Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies: A Companion to the Classic Cartoon Series by Russell Merritt & J.B. Kaufman